There’s a huge number of things to consider when localizing a game (you can read about some of them here), and one of them is the engine the game was created in. We decided to take a deep dive into the topic of game localization in two of the most popular engines, Unity and Unreal Engine.

Game localization in Unity

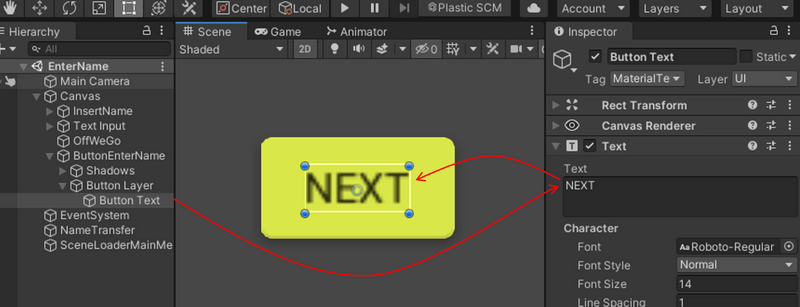

The easiest way to add text to your game in Unity is to make it a property of a UI object. For example, when we create a button, a text object is automatically generated and linked to it. We can then add the text we need (“Next” in the image below), and voilà—the text appears on the button.

This text is saved in a Unity scene file, with the .unity file extension. If our button never changes, then that’s all there is to it. But what if we want the text on the button to change depending on the context? Let’s say we’ve decided to localize our game. This means that we’ll need to instantly switch between translations of all the text elements that appear on the screen as required.

Luckily, there’s no need to painstakingly create dozens of new buttons, tables, and boxes for every language. Instead, we can just link each UI text element up to a text file that contains the phrases we need. These files are called dictionaries. Once we have dictionaries set up, the game will just load the right text from the right dictionary in the right language. Unity supports various text file formats: .txt, .csv, .xliff, .json, .po, and more.

We’ll still have quite a bit of coding to do, though, as our game will need:

- a function that sets the language.

- a function that loads text from the dictionary into the device’s memory.

- a function that transforms the loaded text into a form Unity can understand.

- a function that makes the translated text appear in the game’s interface.

- a localization manager, which is a script that links text objects in a scene up with dictionaries.

- a loading manager, which waits for the localization manager to do its job (when the player chooses a language) before loading a new scene.

Next, a little manual work will be needed to:

- link the localization manager up to every localizable text object.

- assign a script to every text object that gets the key for the right text and puts the localized text in the Text field.

Complicated, isn’t it? Thankfully, Unity recently released its own localization tool, unsurprisingly called Localization (it did exist before, but it was only prereleased in April 2021—and judging by all the bug reports on the tech support forum, it’s still early days). It automates a lot of the localization process, allowing you to set locales and then play sounds and show different strings and images on the screen for each locale. It also carries out “pseudolocalization”, or machine translation, so you can see what the interface will look like in one locale or another. The Localization tool also lets you export data into Google Sheets, not just text files.

But way before the official Localization tool came into being, there were various third-party game localization management plugins, such as the I2 Localization plugin by Inter Illusion. It has similar functionality to Unity’s own tool:

- support for Google Translate.

- automatic search for missing, duplicate, or unused translations.

- support for plurals.

- support for RTL (right-to-left) languages such as Arabic, Hebrew, and other languages.

- non-text object localization (you might need different images or audio files for different languages).

- font and texture management (different object fonts/textures can be set for different languages).

It costs $45.

So that’s languages dealt with. But game text isn’t just about the meanings of words. It’s also about how they look. In game localization, it’s not just what’s inside that counts: exteriors also need attention.

UI Text, Unity’s standard tool for working with text, is very simple and doesn’t support text effects (dynamic reflections, shadow volumes, etc.). To get text effects, you’ll need to use the TextMesh Pro plugin developed by Digital Native Studios. It generates a volume mesh that enables you to apply various effects to text and even create animations. TextMesh Pro was a great success, so Unity acquired it and made it available for free with Unity’s main editor from the 2018 version onwards.

Game localization in Unreal Engine

Unreal Engine has done a much more thorough job of solving localization problems than Unity. It has had its own standard localization tool for a while, so there’s no real need for third-party plugins.

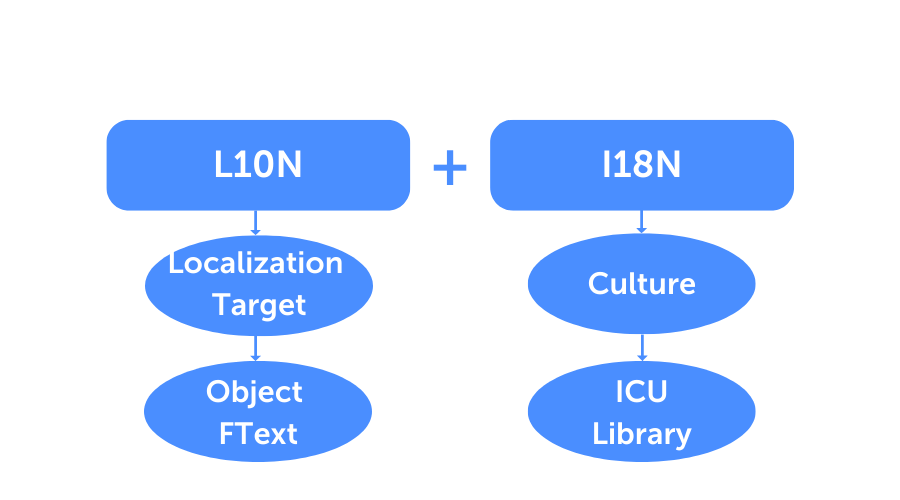

It’s worth bearing in mind that Unreal Engine distinguishes between localization and internationalization. Localization involves adapting a game for a specific region or language by translating the text and adding components specific to the locale, while internationalization refers to developing a game in such a way as to make it easily adaptable for different languages without changes to its architecture.

Localization in Unreal is built around a data type called FText, while internationalization uses the ICU (International Components for Unicode) library.

Unreal refers to the set of rules for formatting text in a particular region as a “culture”. Cultures include rules for:

- handling numbers and special symbols (currency signs, percentages, decimal separators, etc.).

- formatting dates and times.

- using plurals.

Each culture has a code consisting of between one and three parts:

- an obligatory two-letter ISO 639-1 code (such as “zh”).

- a supplementary four-letter ISO 15924 code (such as “Hans”).

- a supplementary two-letter ISO 3166-1 country code (such as “CN”).

This gives us “zh-Hans-CN”, where “zh” means Chinese, “Hans” means Hànyǔ Simplified, and “CN” is the variant of Chinese used in the Republic of China.

The ICU (International Components for Unicode) library:

- asks the operating system what culture to use.

- identifies the correct text direction.

- analyzes any internal restrictions in the text (e.g. string wrapping).

Localizable objects in Unreal can include text (or rather text and fonts), textures, audio and video files, cutscenes, scene sequences, and animations.

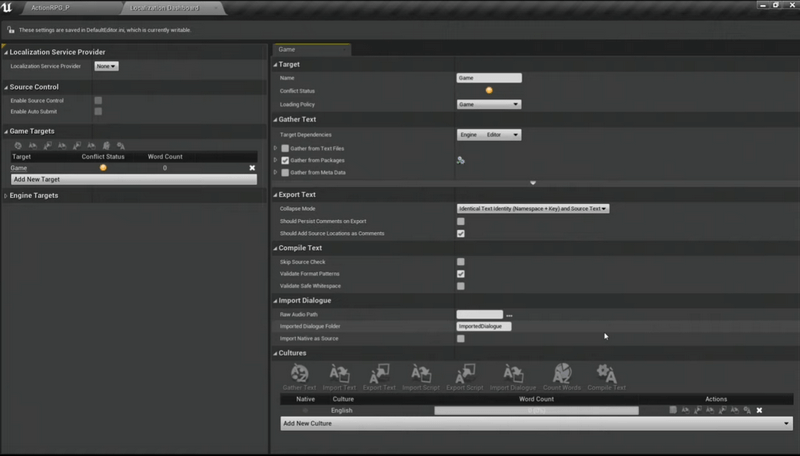

Unreal calls its localization interface the Localization Dashboard.

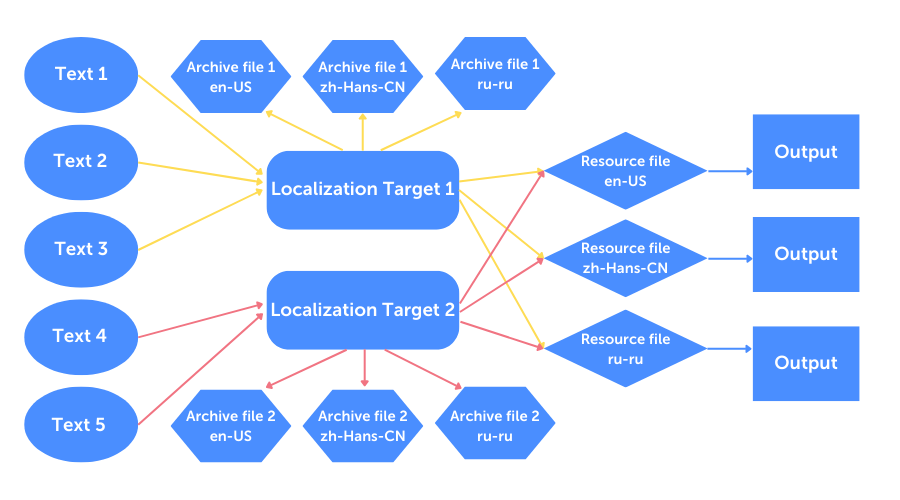

Unreal’s term for modules containing localization data is Localization Targets. These modules contain text taken from a specified set of sources. They are stored in a manifest file, translated in culture-specific archive files, and compiled into culture-specific localization resource files, which are what the game displays. It all looks a bit like this:

Yep, even in Unreal, localization is a tricky business.

The localization process in Unreal generally works like this:

- Text elements (a button with text, a box, etc.) are added to the game.

- A list of cultures for which localization is needed (en-US, ru-RU, etc.) is added.

- Localizable text elements are brought together in the localization system.

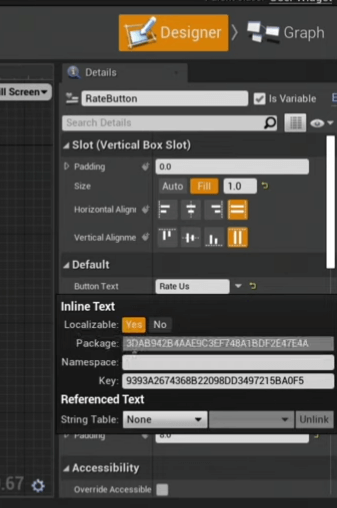

- An FText object is then created for each UI text element. This isn’t just a string of text: it has a special structure that allows you to change cultures on the fly. When an FText object is created and the Localizable parameter is set to Yes (as it is by default), the text element is assigned a key that looks like this: «9567B129548DD2468752BA0F5». This key allows the text element to be identified during localization.

- Unreal’s localization system creates a list of localizable FText objects in the game.

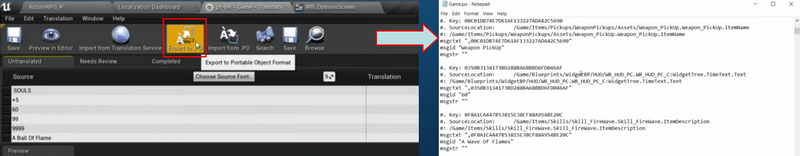

- The localizable UI elements are exported as .po files, translated, and re-imported.

But how does Unreal handle text effects? In 2019, the engine acquired a plugin called Text 3D, which lets you create masterpieces like this:

Text 3D supports font effects such as shadow volumes, beveled and rounded character edges, different distances between symbols/words/strings, proportional scaling, horizontal and vertical alignment, different fonts, letter-by-letter animation, on-the-fly changes to animated text, and much more. Just one caveat: as of 2022, Text 3D is still in beta, so we don’t yet know how much of its functionality will make it into the final version.

If you’d be interested to learn about working with text in other game engines, drop us a line, and we’ll put an overview of the available tools together.