Jon Hare

Journey Through the World of Games

In this episode, we sit down with the legendary Jon Hare, co-founder of Sensible Software, mastermind behind Sensible Soccer, and creative force behind Sociable Soccer. From the early days of pixel-by-pixel graphics on the ZX81 to navigating the shifting tides of game investment and outsourcing, Jon reflects on nearly four decades in the industry with sharp wit and unfiltered honesty. He talks soccer (both virtual and real), dream games that never saw the light of day, the overlooked power of 2D art, and why the game industry desperately needs more curation and fewer NFTs. A must-listen for anyone who ever played Cannon Fodder or wondered how to survive—and thrive—in gamedev for 40 years.

A heads-up for true retro fans: exclusively in the video version, there’s a hidden bonus that’ll let you install a classic game. And if you stick around to the very end, there’s a surprise waiting for you.

Starting Out and Founding Sensible Software

Sensible Software was my first company. My business partner and I started it in the mid-80s, and we sold it in 1999 to Codemasters. I’ve been in this industry for a long time—since 1985—and I’ve had the chance to wear many hats: artist, musician, designer, producer, and company director. Over the years, I’ve been involved in a wide variety of games and collaborations. After Sensible Software, I did consulting for different companies. Then in 2004, I founded Tower Studios, which I ran solo until just recently. In fact, I sold it just over a month ago. Most of my recent work has been on Sociable Soccer, which has taken up the last eight years of my life. It’s been quite the journey. You go from working in your bedroom on pixel games to running long-term live operations. The industry’s changed massively—but in a way, not that much. Passion, good ideas, and tight execution are still what matters most.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Source: en.wikipedia.orgPong at a School Fair: The First Game He Played

When I was about eight years old—this was around 1974—there was a school fair, like a fête, with games and activities: bash-the-rat, throw-the-ball-in-the-hole kind of stuff. But someone brought in an early version of Pong on a TV, and that was the first time I ever saw or played a video game. I didn’t think of it as the future or a career. I just wanted to win because I’m competitive. It was novel, something completely different. I didn’t even know what platform it ran on. I didn’t see another game for a few years after that. So, no—I didn’t fall in love with games instantly or dream of making them. I was more into music and physical games like Subbuteo.

Source: www.shutterstock.com

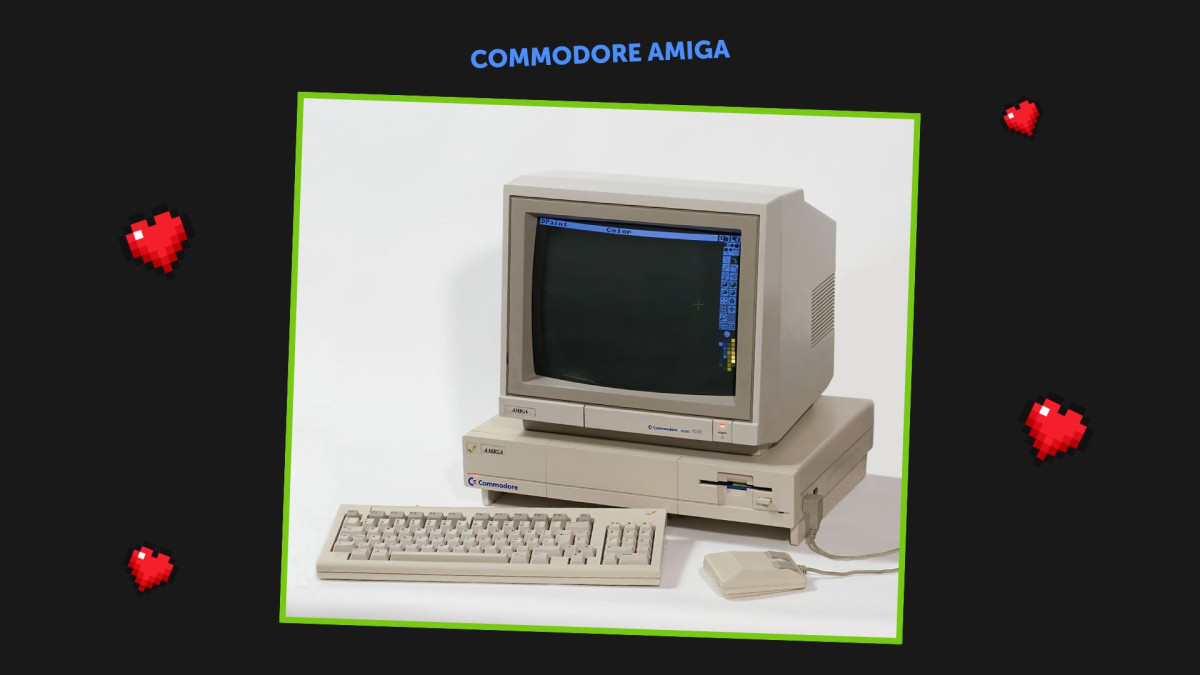

Source: www.shutterstock.comFavorite Platform: Why the Amiga Was Revolutionary

Without hesitation, the Commodore Amiga was my favorite machine. It was such a leap forward in what we could do creatively. It had better sound, graphics, and memory—and most importantly, it gave us freedom. No gatekeeping from platform holders. No one telling us what we could or couldn’t make. It was just pure creative freedom. We could make anything, experiment with mechanics, styles, interfaces—and it was easy to develop for. In hindsight, I think a lot of the magic from the Amiga era came from how open and technically friendly the platform was. Compared to modern platforms that are locked behind SDKs, approval processes, and monetization concerns, the Amiga felt like a playground. That’s why most of our best work came out on it.

Source: www.popularmechanics.com

Source: www.popularmechanics.comFrom Music to Pixel Art: Entering the Industry

Chris Yates and I were musicians before anything else. We were writing songs together and playing in bands. But one day, I visited Chris, and he was programming a game on a ZX81. He needed help with the art, and I’d studied art, so I jumped in. The company he was working with liked what I did and offered me a job too. That’s how it all started. We transitioned from music into game development almost accidentally. We didn’t know it would become a career. We were just trying to do cool stuff and pay the bills. It was a very DIY era. People taught themselves everything: code, art, design. We were the first generation to become game developers. There were no templates, no schools, no industry standards. Just raw talent, hustle, and luck.

Source: talkingames.com

Source: talkingames.comPixel-by-Pixel Art and the Enduring Value of 2D

In the early days, doing game art meant literally controlling every pixel. There were no tools. You drew sprites—8×8 or 16×16—in raw code or on very limited editors. We didn’t have millions of colors or layers. It was all about maximizing with as little as possible. So we learned tricks—shading, drop shadows, visual illusions—that modern artists often skip over. I look at a lot of young artists now and think they’re great with tools, but I wonder if they really understand composition, balance, and structure. 2D art is still crucial. Every game needs menus, icons, and UI. It’s not glamorous, but it’s everywhere. And honestly, in every project I’ve ever worked on—even 3D-heavy ones—there was always a shortage of good 2D artists.

Demoscene Legacy: How His Font Got Famous

I never considered myself part of the demoscene, but I’ve worked with a lot of people who were. Years after Parallax, I found out the font I’d drawn—just the simple A to Z for the game’s interface—became one of the most reused fonts in demoscene history. That blew my mind. I had no idea it was famous! In Finland and Poland, where I’ve worked closely with teams, demo culture is a badge of honor. I respect it, but I always thought the scene’s biggest weakness was that it trains people to obsess over one cool trick. In game dev, you need to finish a full product. It’s not enough to have one beautiful shader or perfect animation. A game is like a city—everything has to work together.

Pirate Radio: Broadcasting Games in Poland

This is one of my favorite stories. At Pixel Heaven in Warsaw, some local retro gamers told me how, back in the 80s, the Polish national radio would actually broadcast black market games over the air. Full programs! You’d sit with your cassette recorder, record the signal, and boom—you had a pirated game. It was state-sponsored piracy. Incredible. I’ve heard similar things from Dutch developers. There was no sense of IP law or copyright enforcement in those days. It was just about getting access. It sounds like sci-fi now, but it was real—and widespread.

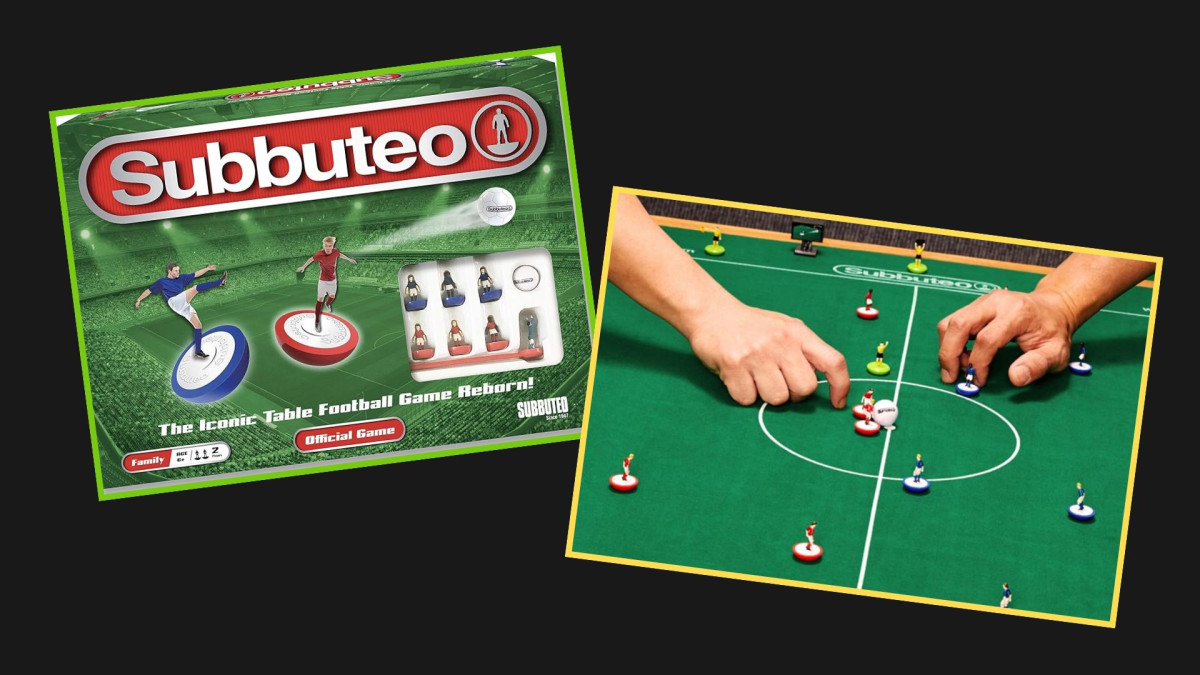

Soccer Roots and Inspiration for Sensible Soccer

I was into [European] football before games. I supported Arsenal for the simple reason that they wore yellow in the 1971 FA Cup final, my favorite color as a kid. Later, I switched to Norwich City and have stuck with them ever since. My love for football wasn’t just watching it. I played it, followed teams, collected kits, and most of all, played Subbuteo. That game, where you flick little plastic players on a cloth pitch, was huge in our house. I’d have it set up and wait for my dad to come home to play. That kind of obsessive daily play, and the longing to play when no one else was available, definitely inspired me. Sensible Soccer was born out of that.

Source: amazon.co.uk, doncasterfreepress.co.uk

Source: amazon.co.uk, doncasterfreepress.co.ukThe Magic of Sensible Soccer’s Instant Success

With Sensible Soccer, after just two months, we had this surreal moment where everyone on the team looked at each other and said, “This is it. This is really good.” That almost never happens. Normally, you tweak for months—too fast, too slow, controls not right—but this one just landed immediately. We were smart about it, too. We locked down the best parts of the code so we wouldn’t ruin them by overthinking. It felt like we’d captured lightning in a bottle. It became our biggest hit by far. Looking back, I think it was the combination of simplicity, responsiveness, and personality. It wasn’t just a football sim; it had soul. That’s the only time in my career we knew from so early on that we had a hit.

Dream Projects That Never Got Released

I have a graveyard of brilliant ideas. Sex, Drugs & Rock’n’Roll was a point-and-click about being in a band. I spent four years on it, and it never saw daylight. CCTV was a surveillance puzzle game, like Where’s Wally meets Orwell. You monitored feeds, identified criminals, and followed conspiracy threads. It was unique, but again, unreleased. Cannon Fodder 3 had branching missions and squad loadouts, but no launch. We had Console Olympics, a comedy sports game with mismatched athletes. Even Touchstone, a surreal adventure about saving your wife by traveling through her body and soul. That one was signed by Origin! But all of them, every single one, got stuck. Sometimes it’s funding, sometimes timing. Sometimes people just don’t get your vision. That’s the heartbreak of creativity.

Running a Lean Studio and Smart Outsourcing

Tower Studios was just me. One employee: me. That way, I avoided overhead. If there was no money, I didn’t pay myself. But outsourcing was essential. We had teams in Finland, and now in the UK, doing core dev. We outsourced console ports, backend servers, localization, QA—everything. We even doubled the UK team recently. The trick is finding people who are both reliable and affordable and fit with your culture. You try, fail, learn. You ask around. You look at their past work. You negotiate smart deals. Running a game company is about surviving lean years and riding the good ones. That’s the cycle.

NFT Crash and the Chain Reaction of Broken Funding

The last few years have been brutal for devs, especially small studios. Why? Because all the funding got sucked into blockchain and NFT hype. Investors chased this mirage of instant 20x returns. And when it collapsed—which it obviously would—the real developers were left without backing. The whole money chain broke. Publishers stopped signing, devs stopped hiring, outsourcers got cut. It’s a domino effect. You can trace it all back to the moment money got hijacked by fantasy tech. Hopefully, we’re coming out of it now. We just got investment and joined a media group. But it took patience and luck and proving that Sociable Soccer was worth backing.

Source: www.sociablesoccer.com

Source: www.sociablesoccer.comAI in Game Dev: Threat or Tool?

AI is already replacing certain jobs, especially anything repetitive or mechanical. Populate a spreadsheet? Done. Generate 50 item descriptions? Done. Concept art is at risk, too—that’s a big one. But the smart artists will use AI as a co-pilot, not a rival. AI doesn’t give you exactly what you want. It gives you 20 cool ideas. Then a great artist refines one of them into something powerful. Same with music, same with scripting. I think the most exciting potential is AI as your personal assistant, fixing your tech issues, organizing files, syncing build tools, deploying updates. If AI can make my computer work flawlessly, that’s a win. Then we can focus on what humans are good at: nuance, intuition, and soul.

A Dream Game About Politics, Religion, and Real Power

What I’d really love to make is a game that simulates global systems—politics, religion, power—and lets players explore alternate realities. What if you banned fossil fuels? What if you ended all religion? What if no one could immigrate? Let’s see what happens. Not preach, not judge—just simulate. But no publisher touches those themes. Sony, Apple, Nintendo—they all avoid anything risky. We’ve been culturally neutered. The world is run by corporations who want predictability, not art. But imagine a game where you could rewind to 1800, make one change, and follow the consequences. That would be radical. And also meaningful. And yes—controversial.

Industry Future: We Need Curators, Not Chaos

The biggest problem we have is that the App Store and Steam are flooded with thousands of games, and most are poor. There’s no curation, no structure. It’s like throwing amateur musicians on the same stage as seasoned pros. In football, not everyone plays in the Premier League. Why are games different? We need tiers: indie, pro, experimental. We need proper tags, proper discovery. Right now, good games disappear into the void because the system values volume, not quality. Companies like Apple and Google don’t care; they just want more content to sell hardware. But if you want this to be a sustainable art form, we need to protect craftsmanship. Not every game needs to please everyone. It’s okay to have niches. What we need is space—and respect—for quality.